There are more than 3,900 confirmed planets beyond our solar system. Most of them have been detected because of their “transits” — instances when a planet crosses its star, momentarily blocking its light. These dips in starlight can tell astronomers a bit about a planet’s size and its distance from its star.

But knowing more about the planet, including whether it harbors oxygen, water, and other signs of life, requires far more powerful tools. Ideally, these would be much bigger telescopes in space, with light-gathering mirrors as wide as those of the largest ground observatories. NASA engineers are now developing designs for such next-generation space telescopes, including “segmented” telescopes with multiple small mirrors that could be assembled or unfurled to form one very large telescope once launched into space.

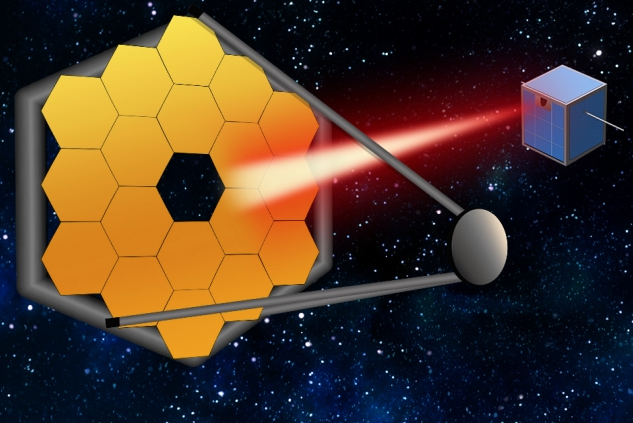

NASA’s upcoming James Webb Space Telescope is an example of a segmented primary mirror, with a diameter of 6.5 meters and 18 hexagonal segments. Next-generation space telescopes are expected to be as large as 15 meters, with over 100 mirror segments.

One challenge for segmented space telescopes is how to keep the mirror segments stable and pointing collectively toward an exoplanetary system. Such telescopes would be equipped with coronagraphs — instruments that are sensitive enough to discern between the light given off by a star and the considerably weaker light emitted by an orbiting planet. But the slightest shift in any of the telescope’s parts could throw off a coronagraph’s measurements and disrupt measurements of oxygen, water, or other planetary features.

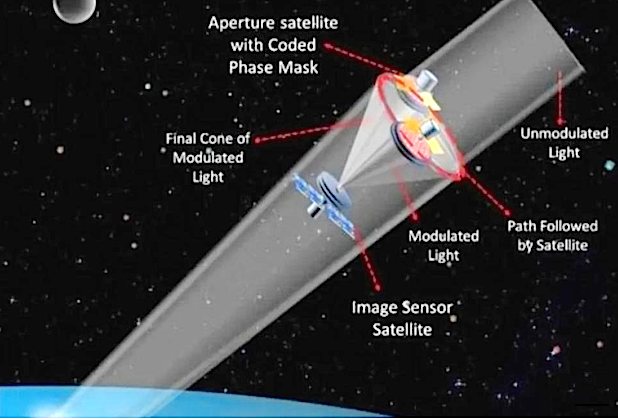

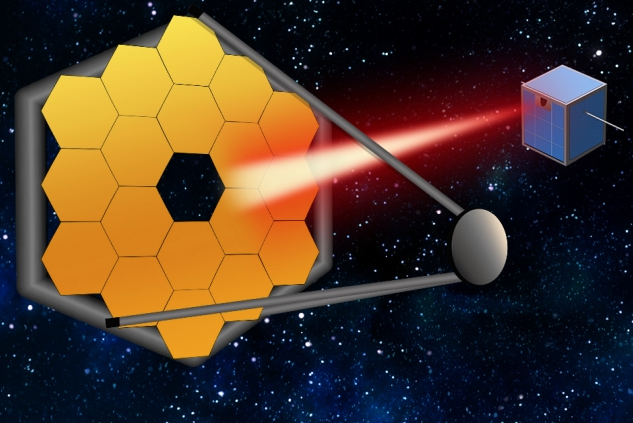

Now MIT engineers propose that a second, shoebox-sized spacecraft equipped with a simple laser could fly at a distance from the large space telescope and act as a “guide star,” providing a steady, bright light near the target system that the telescope could use as a reference point in space to keep itself stable.

In the coming decades, massive segmented space telescopes may be launched to peer even closer in on far-out exoplanets and their atmospheres. To keep these mega-scopes stable, MIT researchers say that small satellites can follow along, and act as “guide stars,” by pointing a laser back at a telescope to calibrate the system, to produce better, more accurate images of distant worlds. Image: Christine Daniloff, MIT

In a paper published today in the Astronomical Journal, the researchers show that the design of such a laser guide star would be feasible with today’s existing technology. The researchers say that using the laser light from the second spacecraft to stabilize the system relaxes the demand for precision in a large segmented telescope, saving time and money, and allowing for more flexible telescope designs.

“This paper suggests that in the future, we might be able to build a telescope that’s a little floppier, a little less intrinsically stable, but could use a bright source as a reference to maintain its stability,” says Ewan Douglas, a postdoc in MIT’s Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics and a lead author on the paper.

The paper also includes Kerri Cahoy, associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics at MIT, along with graduate students James Clark and Weston Marlow at MIT, and Jared Males, Olivier Guyon, and Jennifer Lumbres from the University of Arizona.

In the crosshairs

For over a century, astronomers have been using actual stars as “guides” to stabilize ground-based telescopes.

“If imperfections in the telescope motor or gears were causing your telescope to track slightly faster or slower, you could watch your guide star on a crosshairs by eye, and slowly keep it centered while you took a long exposure,” Douglas says.

In the 1990s, scientists started using lasers on the ground as artificial guide stars by exciting sodium in the upper atmosphere, pointing the lasers into the sky to create a point of light some 40 miles from the ground. Astronomers could then stabilize a telescope using this light source, which could be generated anywhere the astronomer wanted to point the telescope.

“Now we’re extending that idea, but rather than pointing a laser from the ground into space, we’re shining it from space, onto a telescope in space,” Douglas says. Ground telescopes need guide stars to counter atmospheric effects, but space telescopes for exoplanet imaging have to counter minute changes in the system temperature and any disturbances due to motion.

The space-based laser guide star idea arose out of a project that was funded by NASA. The agency has been considering designs for large, segmented telescopes in space and tasked the researchers with finding ways of bringing down the cost of the massive observatories.

“The reason this is pertinent now is that NASA has to decide in the next couple years whether these large space telescopes will be our priority in the next few decades,” Douglas says. “That decision-making is happening now, just like the decision-making for the Hubble Space Telescope happened in the 1960s, but it didn’t launch until the 1990s.'”

Star fleet

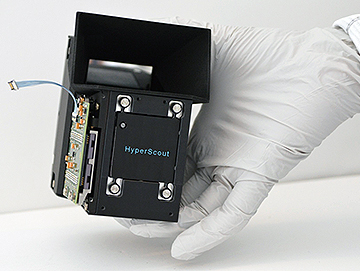

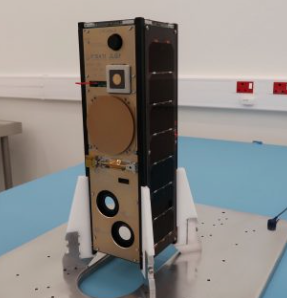

Cahoy’s lab has been developing laser communications for use in CubeSats, which are shoebox-sized satellites that can be built and launched into space at a fraction of the cost of conventional spacecraft.

For this new study, the researchers looked at whether a laser, integrated into a CubeSat or slightly larger SmallSat, could be used to maintain the stability of a large, segmented space telescope modeled after NASA’s LUVOIR (for Large UV Optical Infrared Surveyor), a conceptual design that includes multiple mirrors that would be assembled in space.

Researchers have estimated that such a telescope would have to remain perfectly still, within 10 picometers — about a quarter the diameter of a hydrogen atom — in order for an onboard coronagraph to take accurate measurements of a planet’s light, apart from its star.

“Any disturbance on the spacecraft, like a slight change in the angle of the sun, or a piece of electronics turning on and off and changing the amount of heat dissipated across the spacecraft, will cause slight expansion or contraction of the structure,” Douglas says. “If you get disturbances bigger than around 10 picometers, you start seeing a change in the pattern of starlight inside the telescope, and the changes mean that you can’t perfectly subtract the starlight to see the planet’s reflected light.”

The team came up with a general design for a laser guide star that would be far enough away from a telescope to be seen as a fixed star — about tens of thousands of miles away — and that would point back and send its light toward the telescope’s mirrors, each of which would reflect the laser light toward an onboard camera. That camera would measure the phase of this reflected light over time. Any change of 10 picometers or more would signal a compromise to the telescope’s stability that, onboard actuators could then quickly correct.

To see if such a laser guide star design would be feasible with today’s laser technology, Douglas and Cahoy worked with colleagues at the University of Arizona to come up with different brightness sources, to figure out, for instance, how bright a laser would have to be to provide a certain amount of information about a telescope’s position, or to provide stability using models of segment stability from large space telescopes. They then drew up a set of existing laser transmitters and calculated how stable, strong, and far away each laser would have to be from the telescope to act as a reliable guide star.

In general, they found laser guide star designs are feasible with existing technologies, and that the system could fit entirely within a SmallSat about the size of a cubic foot. Douglas says that a single guide star could conceivably follow a telescope’s “gaze,” traveling from one star to the next as the telescope switches its observation targets. However, this would require the smaller spacecraft to journey hundreds of thousands of miles paired with the telescope at a distance, as the telescope repositions itself to look at different stars.

Instead, Douglas says a small fleet of guide stars could be deployed, affordably, and spaced across the sky, to help stabilize a telescope as it surveys multiple exoplanetary systems. Cahoy points out that the recent success of NASA’s MARCO CubeSats, which supported the Mars Insight lander as a communications relay, demonstrates that CubeSats with propulsion systems can work in interplanetary space, for longer durations and at large distances.

“Now we’re analyzing existing propulsion systems and figuring out the optimal way to do this, and how many spacecraft we’d want leapfrogging each other in space,” Douglas says. “Ultimately, we think this is a way to bring down the cost of these large, segmented space telescopes.”

by Jennifer Chu for MIT News ###

This research was funded in part by a NASA Early Stage Innovation Award.

Related links

PAPER: “Laser guide star for large segmented-aperture space telescopes, part 1: Implications for terrestrial exoplanet detection and observatory stability.” http://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/1538-3881/aaf385/meta

ARCHIVE: Laser-pointing system could help tiny satellites transmit data to Earth http://news.mit.edu/2018/laser-pointing-system-satellites-transmit-data-1214

ARCHIVE: E.T., we’re home http://news.mit.edu/2018/laser-attract-alien-astronomers-study-1105

ARCHIVE: For collecting weather data, tiny satellites measure up to billion-dollar cousins http://news.mit.edu/2018/for-collecting-weather-data-cubesats-measure-up-0927

ARCHIVE: Space junk: The cluttered frontier http://news.mit.edu/2017/space-junk-shards-teflon-0619